Kondratyuk Poltava Polytechnic”.

On July 9, 2025, mothers raising children with disabilities visited Poltava Polytechnic for an art therapy session organised by the university's practical psychologist, Olena Kryvenko, Associate Professor of the Department of Psychology and Pedagogy, Maryna Teslenko, and Senior Lecturer of the Department of Fine Arts, Olena Ostrohliad. The session is part of the international, large-scale EU-funded Erasmus+ KA220-ADU project “TRUST” – Trauma of refugees in Europe: An approach through art therapy as a solidarity program for Ukraine war victims (Grant No. 2024-BE01-KA220-ADU-000257527).

The project title is decoded as follows:

TRUST

T – Trauma

R – Refugees

U – Ukraine

S – Solidarity

T – Therapy

The project is co-funded by the EU and led by the Centre Neuro Psychiatrique St-Martin from Belgium, in partnership with the National University “Yuri Kondratyuk Poltava Polytechnic” (Ukraine), Greek Carers Network EPIONI (Greece), Fondazione Don Luigi Di Liegro (Italy), Lekama Foundation (Luxembourg), EuroPlural Project (Portugal).

During the session, participants discussed how the current realities – war, uncertainty, and the loss of safety – complicate daily life, amplifying anxiety that drains internal resources and makes it difficult to stay in touch with oneself. Special attention was paid to the experiences of mothers raising children with disabilities. Their daily lives are filled with challenges that require constant emotional investment and care for others. In the context of war, this leads to chronic tension, increased feelings of guilt, anxiety, and exhaustion. In such conditions, it becomes crucial to allow oneself to experience any emotions, even those that society often deems “negative,” such as fatigue, irritation, fear, or despair.

The participants were supported in recognising that accepting one’s own emotions and practising self-care is not selfishness but a necessary condition for maintaining life energy to care for their children and overcome everyday difficulties.

A guided meditation-visualisation titled “We Don’t Always Need to Know About…” served as a symbolic transition from recognising emotional burdens to creating a space for renewal. It helped participants release their excessive need for control and develop trust in their inner resources.

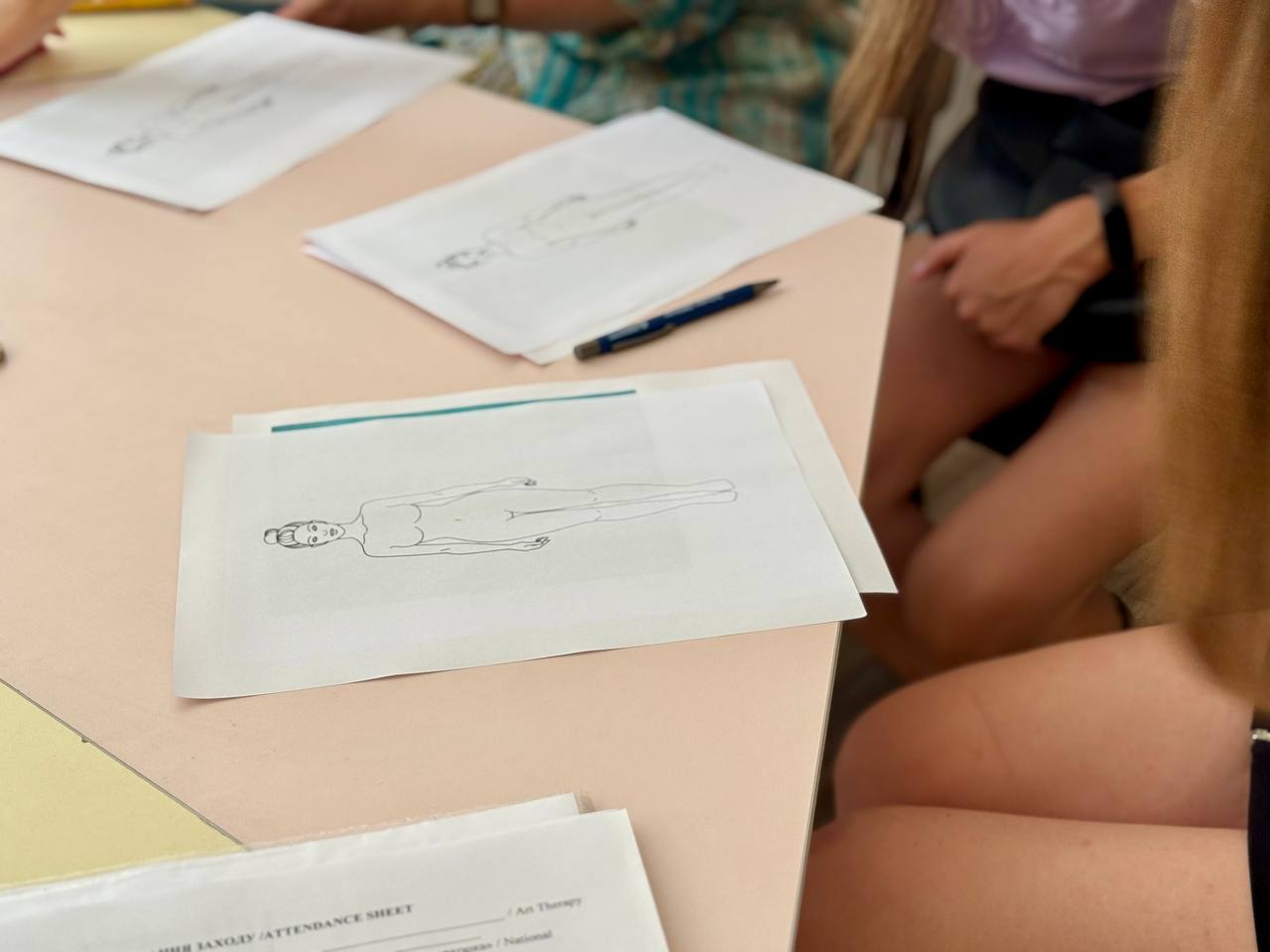

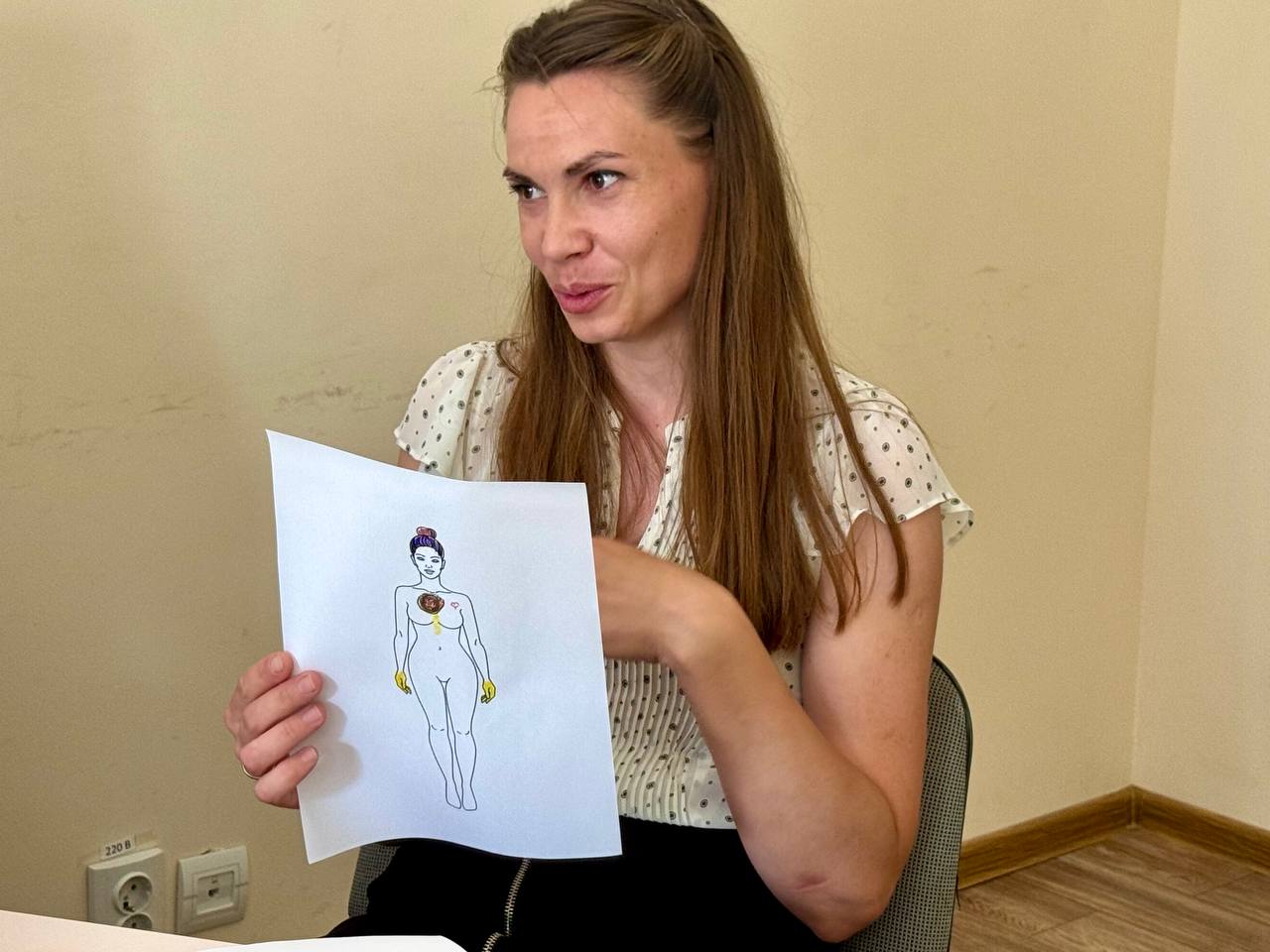

We explored the question: “Where does emotion live in the body?” During an art therapy exercise, the women worked with their bodies as “maps” of emotion. Each was given a body silhouette to colour according to their sensations. They could also add lines, spots, symbols – anything that helped name and release accumulated feelings.

Deep personal insights emerged in the process:

“I saw what my anxiety looks like for the first time…”

“I realised where my fatigue lives – in my legs and arms.”

“I finally saw that my thoughts look like a black cloud in my head.”

“This little fire inside – it doesn’t burn; it warms…”

The participants weren’t just drawing – they were learning to recognise body signals, notice ignored emotions, and find inner resources through colour, touch, and mindful attention. They discovered that bodily awareness leads to emotional literacy, and gentle self-compassion leads to newfound strength.

The women then worked with the metaphor of the “Inner Garden”, a powerful image in art therapy that symbolises a personal space where one can nurture, grow, and restore one's inner strength. For mothers of children with disabilities, who face daily burnout and chronic stress, now compounded by the burden of wartime anxiety, this metaphor provided a way to separate their personal space from external struggles symbolically. It allowed them to reconnect with their often-overlooked inner resources and create a visual image of peace, harmony, and safety, offering hope and strength for continued resilience.

The participants were invited to create an image of their inner garden, reflecting their current emotional state, needs, dreams, and strengths. A key element was the freedom to include anything they wished – any plants, landscapes, or elements that brought calm and renewal.

The art therapy session “My Inner Garden”, held for mothers navigating difficult life circumstances, became a deep and multifaceted practice of emotional healing. The participants created symbolic “gardens” where they could retreat from everyday anxiety, find a sense of grounding, and feel at peace.

One of the most important therapeutic effects of the practice was the creation of a safe internal space. For women whose lives revolve around their child and external demands, immersion in the symbolic world of the garden offered safety, stillness, and self-awareness.

Through colours, shapes, and symbols, participants expressed suppressed emotions. Some gardens featured muted tones, dry branches, or wilted flowers – representations of fatigue, sadness, and loss. Others included vibrant flowers, fresh leaves, and water – images of hope, inner light, and the desire for balance.

The garden also became a place of resource activation. Each woman could “plant” symbols of what gives her strength, such as love, patience, faith, and resilience. The creative process helped awaken inner reserves and restore a sense of control and vitality.

The practice served as a form of meditation. The process of creating helped participants pause, calm down, and stay in the moment, an essential tool during ongoing stress. Self-compassion also played a central role: by allowing themselves to create something just for themselves, the women learned to recognise and meet their own needs.

Although the “garden” work was individual, sharing the artwork in the group fostered deep empathy and mutual support. The shared experience built a sense of unity, as each mother knew she was understood. The session left behind not only creative outcomes but also a vital inner realisation – that strength can be cultivated, even amid a storm.

The art therapy session “My Inner Garden” proved to be highly effective for psychological recovery. It allowed participants to create a safe space for self-expression and emotional release, temporarily step away from daily challenges and traumatic circumstances, express repressed emotions (such as fatigue, sadness, and anxiety), and simultaneously activate positive resources (like hope, calm, and vitality). It helped symbolically restore inner balance and a sense of control over their condition, uncover personal sources of strength that support them each day, and strengthen the feeling of community and mutual understanding among mothers with shared experiences.

At the end of the session, participants were invited to a mindfulness practice designed to quiet negative automatic thoughts and cultivate new, helpful beliefs that support psychological resilience, helping them remain present in the moment.

This practice held exceptional value for mothers raising children with disabilities, as it allowed them to briefly release worries associated with constant responsibility and anxious thoughts about the future. Mindfulness helped them focus on the present, connect with their inner strength, and experience a few minutes of peace, free from the expectations and demands that often accompany parenting.

During the exercise, the mothers learned to observe their emotions and thoughts without judgment, treat their feelings with care, and permit themselves to rest, something critically important in their challenging circumstances.

The “TRUST” project continues to demonstrate its vital role in providing psychological support to the most vulnerable groups. More sessions lie ahead, promising new, meaningful practices, practical methods, and – most importantly – genuine support that Ukrainians so desperately need today. Because art is not only about aesthetics, it is about hope – the kind that helps us endure. It is about life that finds a way, even through the deepest cracks.

Media Centre of

National University “Yuri Kondratyuk Poltava Polytechnic”