In September 2023, a series of guest lectures “Contemporary Contexts and Debates: 21st Century Literatures and Cultures in English” by literary experts from Germany, Switzerland, the USA and Canada began on the basis of the Faculty of Philology, Psychology and Pedagogy of the National University “Yuri Kondratyuk Poltava Polytechnic” for students of specialties 035 Philology and 014 Secondary Education of the university. The organizer and moderator of the guest lectures series was Hannah Schoch, a postgraduate student at the University of Zurich.

It should be recalled that the series of guest lectures “Contemporary Contexts and Debates: 21st Century Literatures and Cultures in English” includes various disciplines, such as American studies, English studies, Canadian studies as well as media studies, an overview of a number of modern trends important for understanding literatures and cultures in English. The purpose of these lectures is to understand how literature and popular culture respond to the problems of the 21st century, to give students an understanding of contemporary debates and contexts that are crucial for effective intercultural communication, and to promote a comprehensive understanding of the role of contemporary literature and popular culture in society.

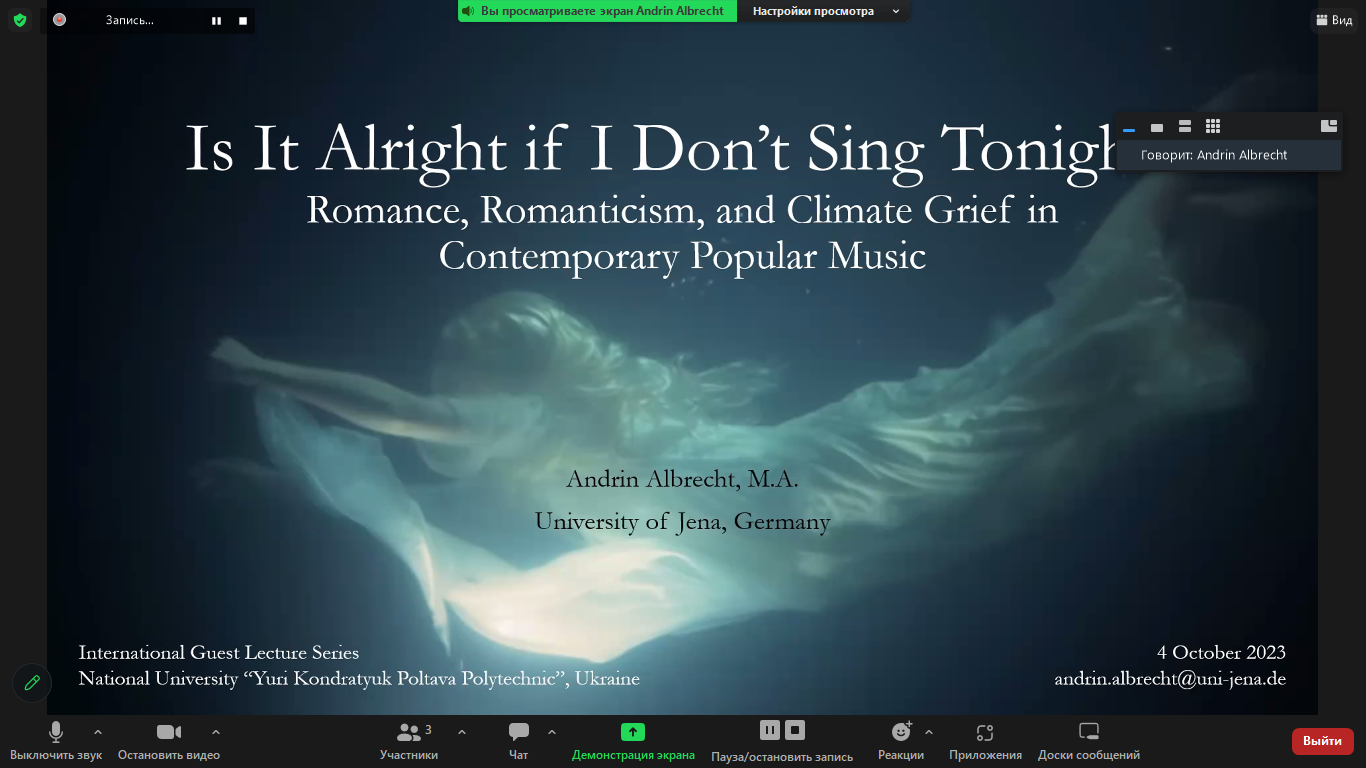

A lecture from the series entitled “Is It Alright if I Don’t Sing Tonight? Romance, Romanticism, and Climate Grief in Contemporary Popular Music” took place on October 4, 2023 in Auditorium 318 of the Poltava Polytechnic in a mixed format.

The lecturer was Andrin Albrecht, a researcher from the Friedrich Schiller University of Jena, a member of the DfG study group “Modell Romantik” (research area: American literature), a writer, poet, composer and literary critic who currently lives in Jena, Germany. His PhD thesis, “Romantic Authorities and the Genius of the White Man after “Moby-Dick”” is devoted to the relationship between the concept of genius and ideas about masculinity, institutional exceptionalism, and race in the works of Herman Melville, Volodymyr Nabokov, Thomas Pynchon, and Mark Z. Danylevskyi. In addition to poetry and short fiction in English and German, Andrin Albrecht has written essays and book chapters on a variety of topics, such as “whiteness” in Stanley Kubrick’s “The Shining”, isolation and urban space in the work of progressive rock musician Steven Wilson, and the Polish series of video games “The Witcher”. Of particular interest to Andrin Albrecht are the nodal points between aesthetic experience, society and politics, as well as issues of multimedia, narratology and the legacy of romanticism in the present.

The lecture was devoted to multimedia romantic trends in contemporary popular music as a form of “climatic grief”, as well as narratology in the conditions of late capitalism, using the example of two pop music albums: “Titanic Rising” by the Californian singer Weyes Blood, which came out in 2019, and “Ignorance” by Canadian indie rock band The Weather Station, released two years later.

Both albums are, among other things, artistic engagements on the topic of climate change, which unwittingly raise a fundamental question of literature: what is the need for literature, poetry, music or art in general? What benefit can they bring? Why do art at all in the face of real problems that seem so much scarier than a few lines of poetry or a few chords played on the piano? Answering these questions, Andrin Albrecht touched on the problems of literature in general, and conducted a historical excursion into poetry, industrialization and romanticism in England at the beginning of the 19th century, as it is precisely the climatic changes that are largely the result of that industrialization and the events that took place in England around 1800 year, indirectly led to the appearance of these two music albums.

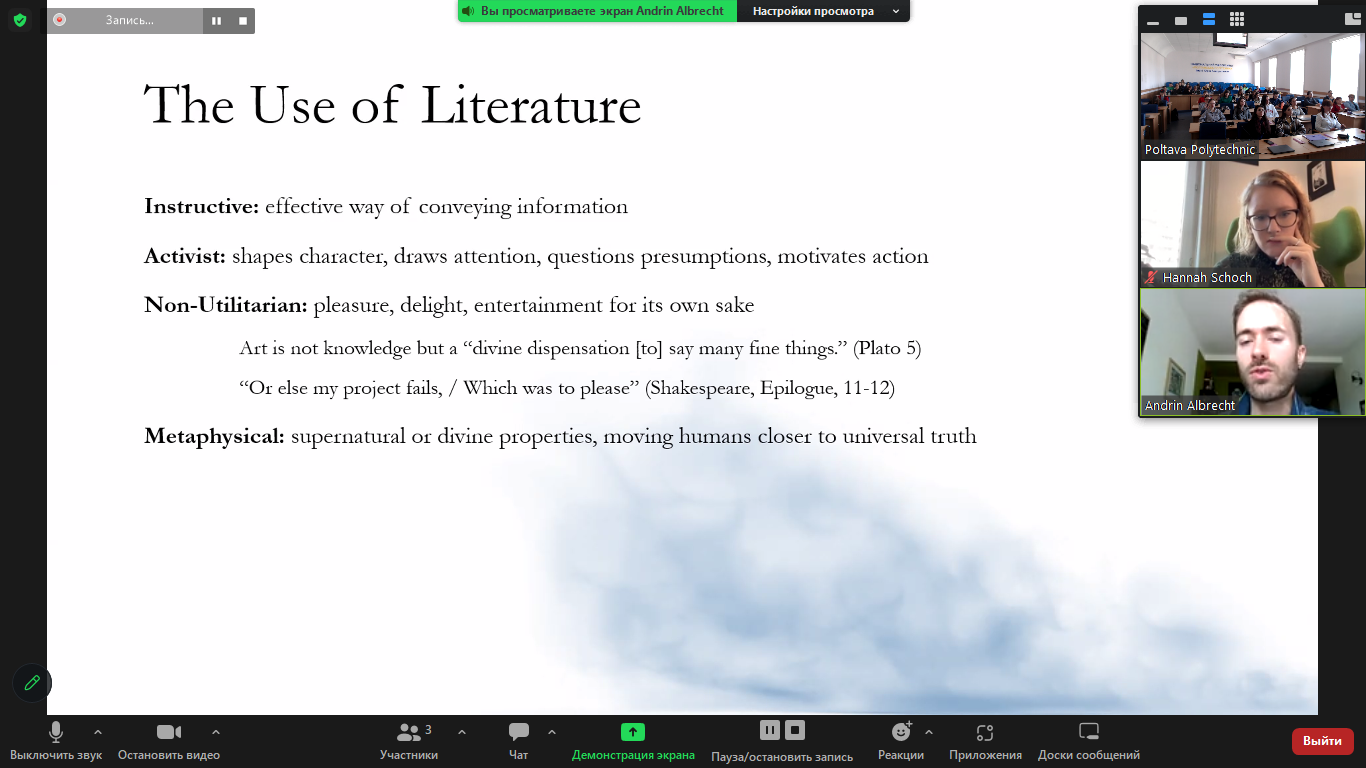

So, the question of the essence and usefulness of literature, as well as the question of what it is needed for, is almost as old as literature itself and was discussed in the works of Plato, Aristotle, all Greek philosophers and almost all philosophers of literature who appeared later. Broadly speaking, attempts to answer this question can be divided into 4 categories: didactic, activist, non-utilitarian, and metaphysical, but all agree that literature is an effective way of conveying information. For example, we read Jane Austen to better understand the social conditions of upper-class young women in Regency England, or a young adult novel about mountaintop mining in the US to learn about destructive mining practices.

Supporters of the “activist” theory claim that exciting stories shape our character and consciousness, make us question things we took for granted, draw attention to issues we were not aware of before, show us how to act, how to think, motivate us to solve social issues, speak truth to power and question established structures, and therefore can really have a political effect. This argument applies, for example, to many works of feminist and postcolonial literature. For example, after the “Black Lives Matter” protests that took place in the United States a few years ago, the sales of writers such as Tony Morris, James Baldwin, and Claudia Rankine skyrocketed, clearly demonstrating the idea that literature can have a moral or political value, that it can help not only to learn about issues, but also to solve them. The third argument is the polar opposite. Some literary critics believe that art and literature are valuable not because they do anything but because they are not supposed to do anything, that they are non-utilitarian, that books are simply beautiful things intended to entertain, move, or impress and that is enough.

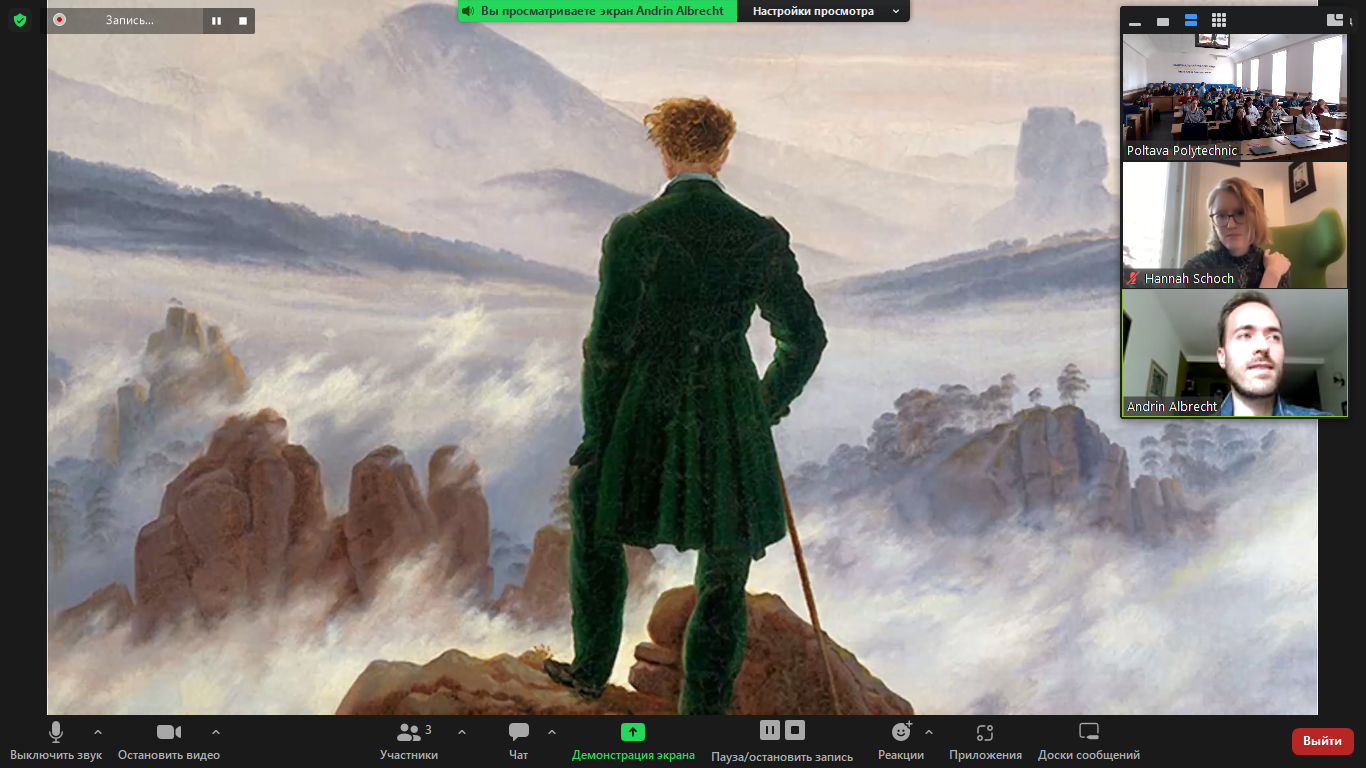

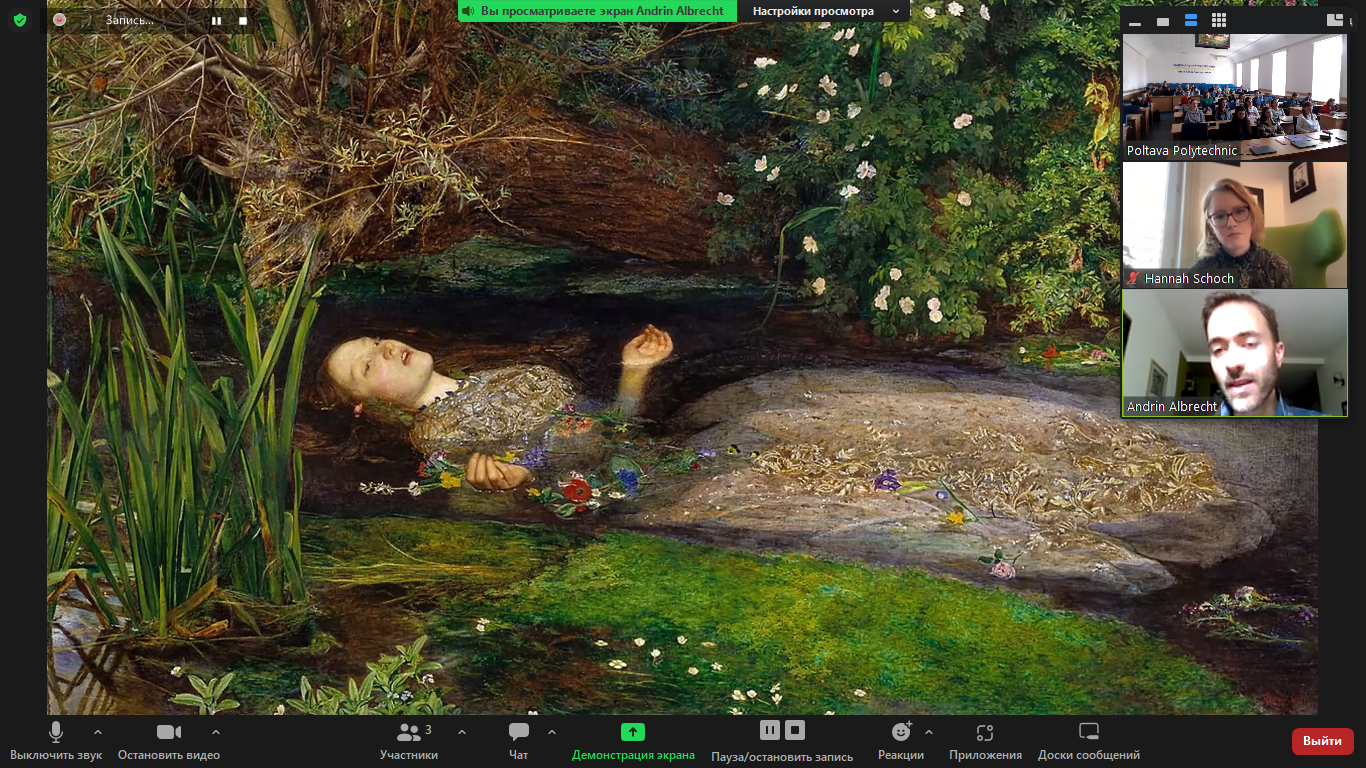

Romanticism became one of the literary directions in which the metaphysical defence of literature was particularly noticeable. Romanticism is a term that everyone comes across in one form or another, and one that seems more complicated the closer you look at it. We usually mean a number of parallel literary, philosophical, artistic and musical currents that existed throughout Europe, the British Isles and the United States around 1800. At that time, these currents were relatively unrelated and heterogeneous. In fact, the term “Romantics” was only used by the Germans to describe themselves, the British romantics were primarily “Lake Poets”, and American romanticism is usually called “Transcendentalism”. However, these terms are largely interchangeable, and they all fall under what we now call the general term “Romanticism”. Among the most famous romantics, we can mention: in the United States – Ralph Waldo Emerson, Edgar Allan Poe, the author of spooky stories, or Nathaniel Hawthorne, in France – Victor Hugo, in Germany – Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich Schiller or the artist Caspar David Friedrich, in Poland – Adam Mickiewicz, in Ukraine – Taras Shevchenko.

So what unites romantics from different fields of art? These are, first of all, huge, untamed, sometimes beautiful, sometimes frightening images of nature, supernatural phenomena and people with supernatural abilities, ghosts, witches, fairies, genius personalities, ruined castles, dream motifs, trials, windows, roads, various fairy-tale motifs. Conventionally, we associate romanticism with a sense of longing, strong emotions, in general with uncertainty about what is real and what is imaginary, with interest in folk traditions, as well as with nationalism and in its dark invariants with madness. And perhaps most important is the fact that Romanticism reached its peak precisely at a time of great political and historical uncertainty.

In 1776, the English colonies on the North American continent won the war for independence and formed one of the world’s first democracies – the United States of America. In 1789, France attempted its revolution through a monarchy, but quickly devolved from democratic ambitions to a reign of terror where tens of thousands of people, including the king and his family, were executed on the guillotine, and then Napoleon Bonaparte emerged, proclaiming himself the emperor and plunged all of Europe into war. Throughout the continent at that time there were revolutionary movements and struggles for independence, but this extreme uncertainty, through which romanticism actually appeared, was not only political, but also economic and environmental. Also in 1776, the British engineer James Watt developed an improved version of the steam engine, which accelerated the Industrial Revolution and gave impetus to industrialization, which spread rapidly across the continent, in England and its colonies, and in a broad sense led to the arrival of the Anthropocene era. “Anthropocene” literally means the era of man. Until that moment, man – Homo sapiens – was only one of the many species that inhabited our planet. The climate changed in one direction or another, sedimentary rocks were deposited, people lived or died without lasting impact on the planetary system. All this changed fundamentally with industrialization and the invention of the steam engine. Suddenly, from burning coal in steam engines, and later from burning gasoline and gas in more advanced engines, so much carbon dioxide was released into the atmosphere that human activity began to affect the climate of our entire planet, the global biosphere, and the composition of its soil. This is what we call the “Anthropocene”. If, for example, a million years later, an alien geologist came down to Earth to collect data about the soil and try to find out its history, then the appearance of the human species would not be recorded in these data. The earth and the composition of the soil would have been exactly the same before and after the appearance of Homo sapiens.

Just like many so-called great civilizations of the past. The Roman Empire, the Aztecs, or the Ming Dynasty would be just one of many species that evolved over millions of years. However, starting around 1800, everything changes dramatically. Of course, the soil is now more acidic, there are remnants of various sediments, plastics, chemicals that won’t just go away, and eventually even radioactivity. And this alien would be able to pinpoint the last 200 years of the human species fairly accurately, while the last 2 million years would look pretty much the same as all the previous time. And so, ancient people actually became a geological factor that changed the future of our planet. The British Isles were at the very centre of industrialization and the spread of the Anthropocene. It was here that James Watt invented and improved the steam engine, and in 1805 the world’s first railway line was built.

With these new technologies came new industrial opportunities: the construction of large factories began, where goods such as textiles or machine parts, even weapons, could be produced much faster and much cheaper than in a traditional workshop. This resulted in rapid urbanization. Rural communities were impoverished and sometimes abandoned almost overnight. People were forced to move to the cities, since only there could they find work. But this work was often in terrible conditions, with a meagre salary that was barely enough to live on. In addition, steam engines’ need for coal led to entire forests being cut down for fuel. Factories began to pollute waterways and cloud the skies over cities. Industrialization brought, on the one hand, enormous technological progress, and on the other, extreme poverty, political instability, and large-scale environmental disasters.

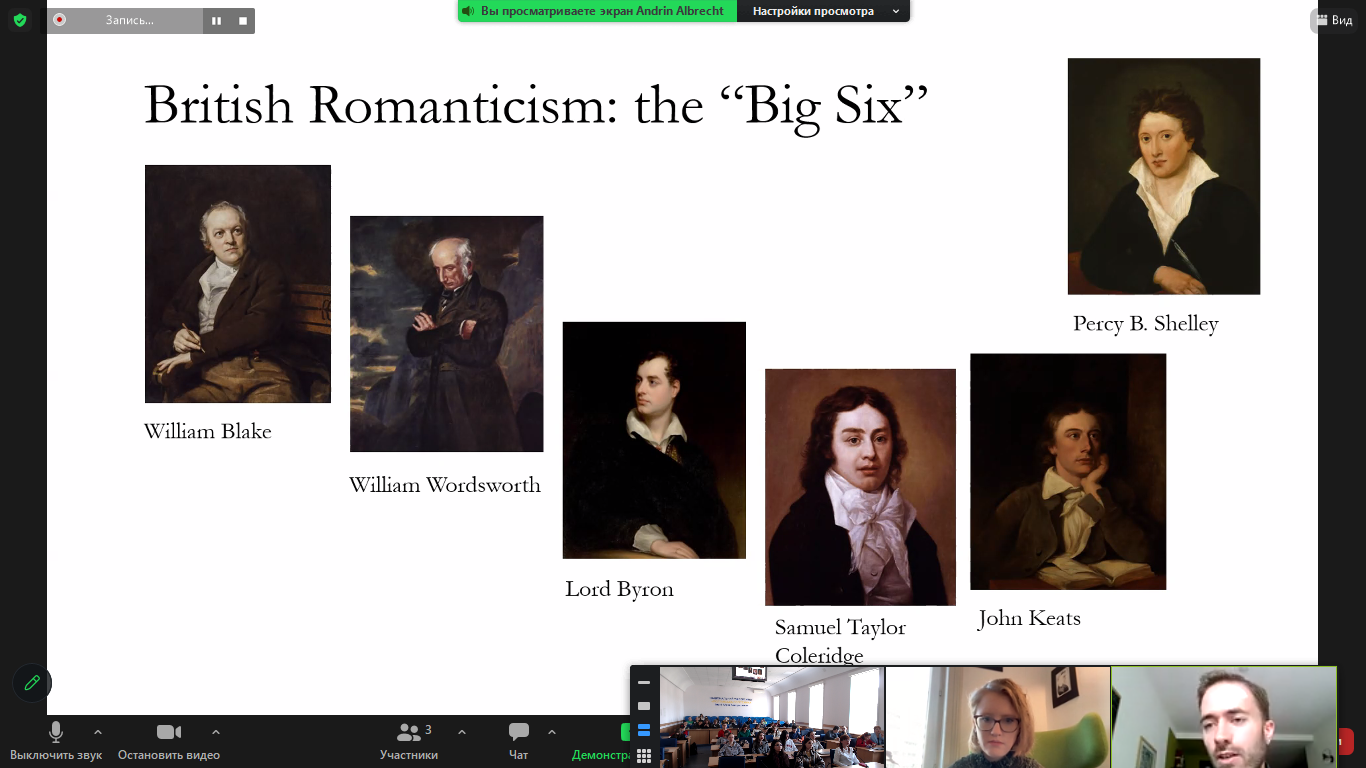

This was the environment in which the British romantics lived and wrote poetry. When we speak of the British Romantics or “Lake Poets” in literary studies, we often refer to the so-called “Great Six” – William Blake, William Wordsworth, Lord Byron, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Keats, and Percy B. Shelley. And although it is believed that the era of romanticism was dominated by male writers, it is worth mentioning at least Mary Shelley, who became very famous as the author of “Frankenstein”, one of the most significant romantic as well as science fiction texts. All these poets, with the exception of John Keats, who was of simple origin, did not have a sophisticated university education and was therefore greatly despised by his contemporaries, were real rock stars of their time. They had a huge following, far larger than any poet today, and all of them, at least in their youth, were politically active.

For example, George Byron died at the age of 37 when he went to Greece to fight in the War of Independence, and Percy B. Shelley was one of the first famous vegetarians in history to come under the scrutiny of the British government for his anti-monarchism and demands for a more egalitarian distribution of wealth. These artists saw the country around them changing, witnessed environmental destruction and social injustice, and yet continued and had to continue writing and publishing poetry about everything in the world. It is now generally accepted that the Romantics firmly believed in the metaphysical use of art. Percy B. Shelley, for example, wrote that poets were considered prophets. Therefore, there is an opinion about poets as creators of prophecies or some divine messengers who are supposed to lead humanity to a higher state of being.

This theory was shared in one form or another by many Romantics of the time, who believed that there was some essence of the world or a higher level of existence that humans might never be able to reach in reality, but could at least approach through art. Hence, in Romanticism appears this feeling of longing and the absence of something important, which is an integral part of many romantic works. However, this idealization of art as some kind of supernatural or divine force is one of the main reasons why Romanticism is sometimes not taken seriously enough as a literary movement, especially in the German-speaking world. In retrospect, it may seem rather naïve that a few young people from extremely privileged backgrounds thought they could change the world by writing a few good lines of poetry. However, one of the most beautiful things about literature is that it can always be interpreted in different ways, and at least one of these interpretations can be correct.

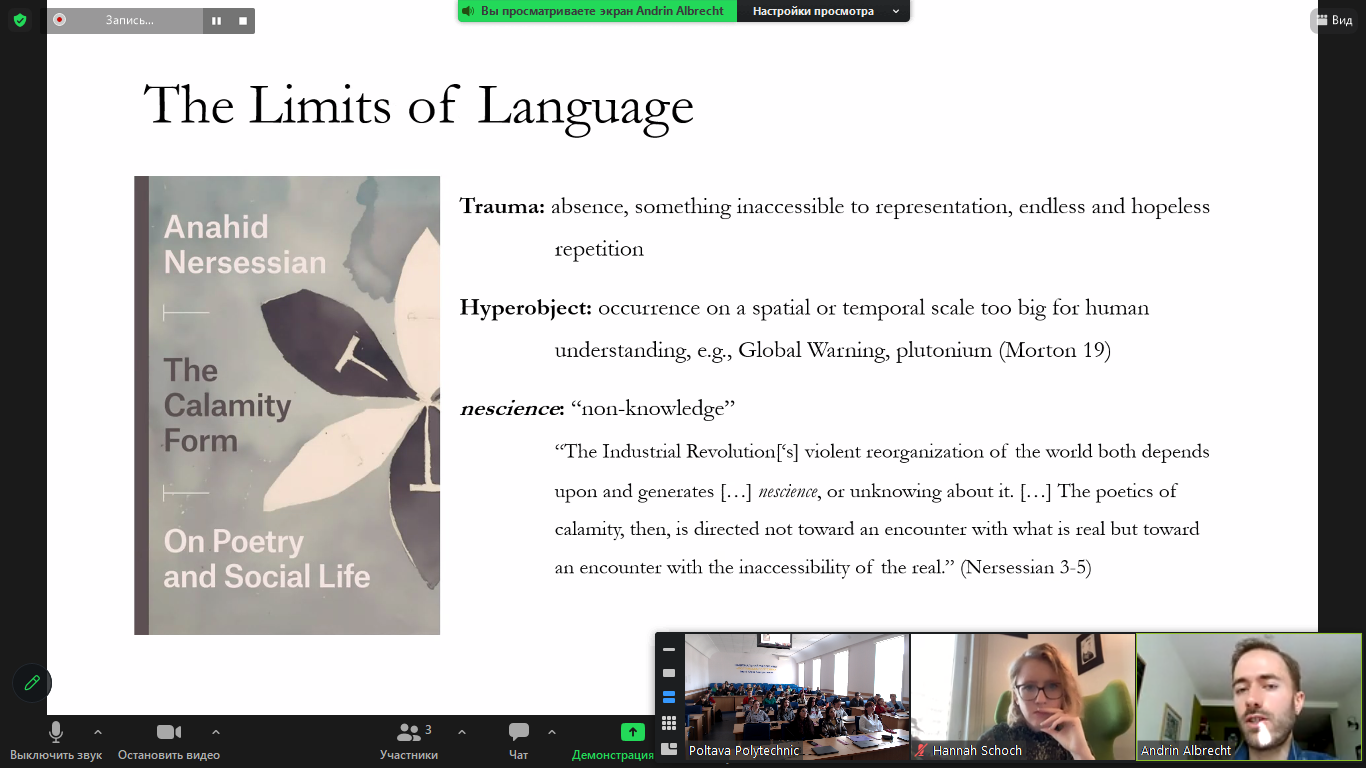

Thus, the American professor of Iranian origin Anahid Nersessian, who teaches literature and, in particular, British romanticism at the University of California in Los Angeles, and works in a field traditionally dominated by white British and American men, published a book in 2020 under entitled “The Calamity Form on Poetry and Social Life”.

What’s more, she lives in a state where wildfires now regularly destroy homes and thousands of acres of forest every summer, and there are days when residents are regularly asked not to go outside without a mask due to the amount of smoke in the sky. So in many ways the economic and environmental conditions in which she lives are very similar, if not worse, than in England during the industrialization and the early romantics. Thus in her book, Anahid Nersessian tries to understand how the poems of someone like William Wordsworth or John Keats could matter in an age of planetary crisis, and what they might have meant in the times when they were written. It is interesting that the author herself is not a romantic and does not believe in the metaphysical idea of some divine power of art or the supernatural ability of art to influence political, economic and geological forces.

Instead, Anahid Nersessian writes that the book is a warning against the heroic possibilities of literature and against taking it too seriously, since poets are as limited as any other cultural figures and any other historical figures in their ability to challenge or undermine the status quo. When it comes to emancipatory politics, culture alone is not a panacea for all ills. At first glance, it sounds quite pessimistic, but Anahid Nersessian claims that art is not an effective weapon against major world problems, although this does not mean that it is worthless, on the contrary, Nersesian suggests that art can confront its own powerlessness and help we have to put up with him. According to Anahid Nersessian, romantic poetry was never intended to change the world, but rather to come to terms with the fact that it cannot be changed with the help of poetry.

Likewise, Timothy Morton, one of the world’s leading literary scholars dealing with climate change, coined the term “hyper object” to denote things that occur on such a vast spatial or temporal scale that the human mind cannot fully grasp them. For example, global warming, which affects the entire globe and every living thing on it, or the element plutonium, a radioactive element that, after its purification, decays after hundreds of millions of years, that is, it exists on a time scale very far from that in which a human can exist. The concept of “hyper object” refers to things that go beyond individual understanding and the capabilities of language. They are beyond the realms of narrative or poetry, or, simply put, they are things against which art has no chance.

Disasters, whether environmental or political, war, pandemic or family tragedy, are in a way traumatic “hyper objects”. They are so overwhelming precisely because we feel there is nothing we can do about them. And that feeling of being depressed can have a lot of really bad consequences. It can paralyse, it can take away the ability to think or act, it can lead to depression, to despair, it can prevent us from resisting injustice or caring for those around us who are in desperate need of care. In the worst case, this feeling can even be fatal. This is as true for people today as it was for young romantic superstars 200 years ago. Despite their privileges, it must have pained them to see forests cut down, rivers polluted, poisons spilled, revolutions and wars broke out, communities impoverished, and to realize that all their poetry, which they admired so much, could do nothing about it.

Anahid Nersessian writes that the industrial level of evolution is a violent reorganisation of the world that creates a sense of inability to understand and act contrary to what is actually happening. Catastrophe projects, thus, are not aimed at meeting the real, but at meeting the unattainability of the real. In other words, poetry is important not because it can change the world, but because it helps us deal with our inability to change things in the real world. It can be comforting, stabilising, powerful, not in a political sense, but in a deeply personal sense.

It is not about the transfer of information. If one wants, for example, to understand the process of climate change, it is much more appropriate to read a scientific article about it than to write a poem about it. As Anahid Nersessian points out, regardless of what Percy Shelley argued, politics is shaped by legislators, executors, soldiers and workers or the collective actions of society, not by poets and their poems. Poetry also has nothing to do with any metaphysical power, but that doesn’t mean it’s useless.

Two music albums – “Titanic Rising” by the Californian singer Weyes Blood, and “Ignorance” by the Canadian indie rock band The Weather Station, fronted by Tamara Lindemann, were recorded almost simultaneously, in the late 2010s, and both represent dramatic changes in the musical lexicon of the respective performers.

The Weather Station’s previous work has mostly consisted of guitar, bass, drums and vocals, but “Ignorance” also features jazz arrangements, strings and woodwinds, two percussionists, a total of 18 musicians comprising to the band. Similarly, “Titanic Rising” sounds like 1970s psychedelic pop, somewhere between Pink Floyd, Enya or Brian Eno, and is far less avant-garde or experimental than Weyes Blood’s previous work.

Moreover, both albums were written as a response to the global planetary climate crisis. In an interview a little over two years ago, Tamara Lindemann, the main songwriter and vocalist of The Weather Station, explained her thought process. She said: “I think, like a lot of people my age, the Climate Crisis is something that’s always been with me. But for the past however many years, it was just this simmering dread feeing in the back of my mind. I couldn’t really look at it; I couldn’t really see it or feel it, and I mostly tried to avoid it. But something shifted in the winter of 2018-2019, where I just actively started reading about it and then I just basically fell down the rabbit hole that happens to you when you really take in the full reality of what it means, and what two degrees of warming means and how far over the cliff we already are. It was a really strange, disorienting experience, to be really engaging with it. I became somewhat obsessed with it. I sort of tried to become an activist in any way I possibly could. And it brought up a lot of really heavy, intense emotions that I felt very isolated in, and I felt kind of foolish for feeling.”

And so Tamara Lindeman decided to write an album called “Ignorance”. “Ignorance” comes from the Latin “Ignorari”, which literally means “not to know”. The author does not try to motivate anyone to activism and does not claim that art or poetry has any spiritual power.

The first track in the album “Ignorance” is called “Robber”. At the beginning of the song, for almost a minute, the drums sound ominously, the low hum of the synthesizer and digitally altered chords can be heard. This means that the first impression we get when we turn on the album is silent, mechanical and disorienting, layer by layer meanings are superimposed and the text acquires new meanings.

This type of growth is one of the key features of industrial capitalism, and it is ultimately the cause of the climate crisis. As more and more instruments appear – strings, pianos, clarinets, they may sound a little more human than drums and electronic soundscapes, but they are also very disorienting sounds. The music gives the impression of people stumbling around aimlessly, without understanding anything, and when Tamara Lindemann finally begins to sing, the first thing that strikes you about the lyrics is the sheer number of different negative forms with which it begins. Also, “Robber” at first sounds like a fairly typical heartbreak lyric, since the robber can be an unfaithful partner, or – metaphorically – a personal mistake, or a rival who stole someone’s significant other.

These tropes are familiar to the listener; so many pop songs are ultimately about heartbreak, broken relationships, betrayal, feelings of disappointment, guilt, regret, and ultimately acceptance that follow a bad breakup. However, in the next stanza, the robber turns out not to be a partner, but a cruel system, namely capitalism. Banks, dinners with white tablecloths, conference centres are mentioned here, all these metaphors of finance and a kind of global interdependence of the economy. The author also constantly uses the anaphora “permission”, creating the feeling of being faced with something again and again, with an onslaught that never seems to stop and never change. At the same time, all the people mentioned in the text, “I”, “you” and “robber” remain so close to each other and almost blurred, sewn together, that they work very well for the image of violent relationships that Lindemann uses. The problem with the industrial system, banks and white tablecloth dinners is that we are all part of it. A robber is someone very close to the person being robbed. It seems like these two have gotten along so well for so long that they benefit from each other, and even now that the betrayal has happened, it’s impossible to just walk away. You can’t just walk away from capitalism and say I’m not going to use products that contribute to climate change anymore. In fact, all of our products, and often the ones we love the most, contribute to it.

The conflict in “Robber” takes place between two elements that are an integral part of each other: individual and collective, strength and weakness. It is very telling that the song ends with the dust rising, which may be one of the key images of the effects of climate change, a confirmation of the drought and what it will ultimately lead to.

The second song to pay attention to is the fourth track on the album, and it’s called “Parking Lot”. This song is much more optimistic than “Robber”. The music sounds almost joyful, the text – desperate. The song seems to embody the possibility of finding joy alongside despair. On the other hand, there is despair in her, there are tears, there is an impossibility to express and describe the trauma that the singer is experiencing, the trauma of the realization that this bird, which she watches in the parking lot, is ephemeral, that it may disappear sooner or later, that somehow the contrast of this beautiful little creature with the movement, the noise, and all the industrialization is too strong to bear. But on the other hand, the little creature is beautiful. The author also uses anaphora, repeats words over and over again: the bird takes off, descends and takes off again. She always sings the same song, but the question it all boils down to is not how we can change it, and not why we don’t do anything. “Is it alright if I don’t sing tonight?” – this is how the key thesis of the song sounds. This is a request for acceptance and perception, because the author and vocalist wants to express with this song that she is powerless now, that it would be wrong to sing in her current state, but she does not fight this feeling, but rather asks if it is normal. Through the song, she openly cries and openly expresses her emotions, she simultaneously wants to remain silent, and confesses her pain, sadness and affliction that she cannot change something, and seeks comfort in the fact that it is possible to grieve with the listeners, even though and not having a solution to the problem, but having the opportunity to share this sense of irresponsibility with the public and to seek solace together in all those joyous things that exist alongside grief.

In general, in her album, the singer uses many stylistic devices, romantic images, such as “dazzling beauty”, which contains a lot of ambivalence and conveys passivity or paralysis in the face of the capitalist machine. In the second half of the song, the image of “climatic grief” becomes more expressive. For example, the term “our light” can refer to electric light used under the laws of war, and to sunlight that produces a greenhouse effect. Burning people remind us of the summer that just passed and was one of the hottest on record, and the tide is one of the effects of climate change that is mentioned most often in her songs.

In the first stanza, one of the most complicated images associated with “climatic grief” appears – the image of a “bottle”. In the imagination of listeners, the sight of plastic bottles on the beach immediately arises.

Of course, the text of the song can be analysed like a regular poem, but the music that plays to it is of great importance for its effect as well. As we saw with the “Parking Lot” example, the end effect can be almost hilarious. But at the same time, this song could be completely gloomy if it was accompanied by, for example, only an ominous synthesizer or a church organ. In addition to music, it is worth mentioning visual elements, such as album covers or music videos, which can tell their own story once again and all these levels intersect in a certain way.

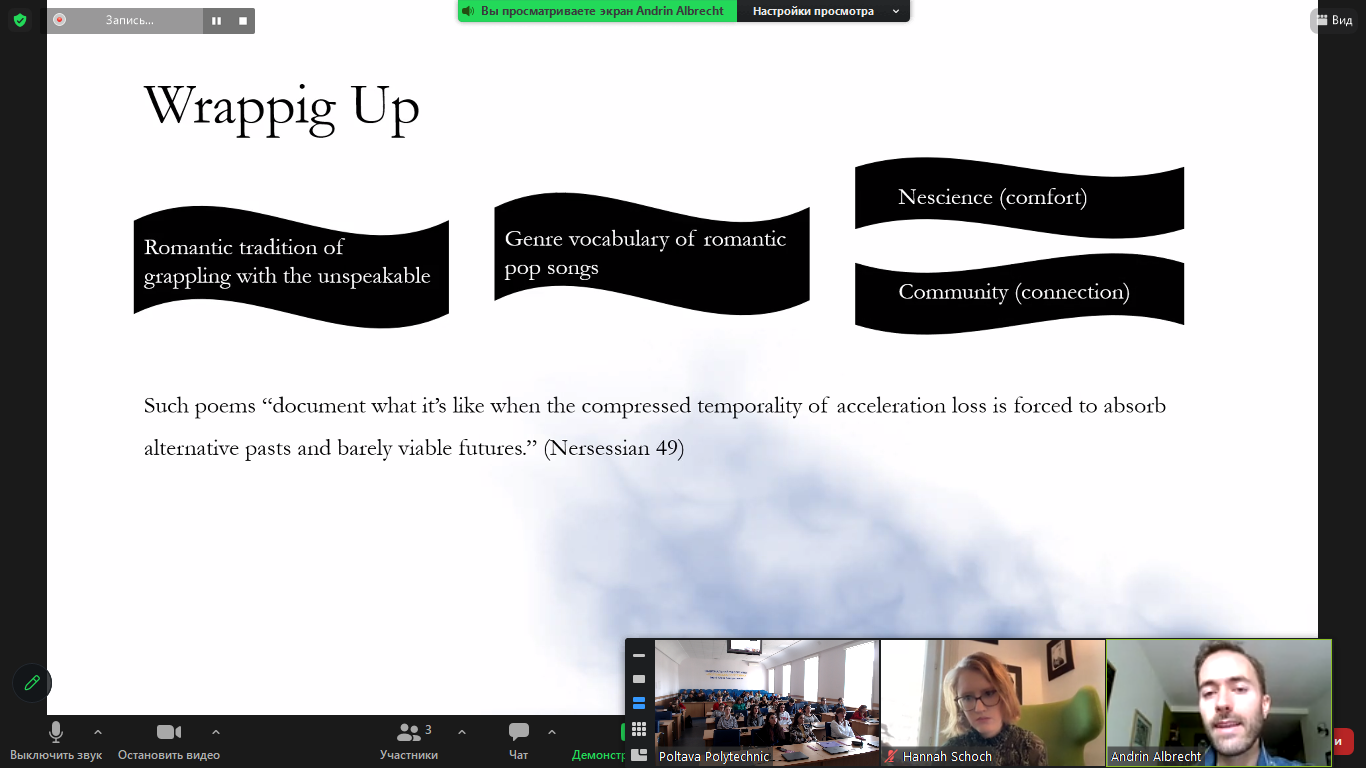

“Titanic Rising” and “Ignorance” are two albums created by artists who live in a place and time of dramatic, terrifying change, uncertainty and impending environmental disaster, much like the British Romantics of the early 19th century. Romantics could not stop industrialization with poetry, any more than modern musicians can protect themselves from climate change with good songs. Thus, both romantics and modern artists focus on their own sense of powerlessness and try to work through it in their work in such a way as to find a way to come to terms with this trauma rather than being consumed by it.

The albums’ writers use motifs familiar from many other pop songs about heartbreak, disappointment, misunderstanding and denial and, ultimately, acceptance. But they reinterpret these motifs from the concept of a failed relationship to the concept of a failed planet, suggesting that human feelings in both contexts are not too different from each other and that larger global problems can be better understood through personal problems. It becomes clear that you are not alone in these feelings, that others, whether they live in California, Canada or England 200 years ago, have experienced very similar emotions. Since works of art are always multi-layered and have many interpretations, each person can find something special in the work, some emotion that they can relate to the same poems or songs.

In a recent interview, Weyes Blood said that different people react very differently to her music, but never put her album aside: “I’ve had climate change deniers tell me they love my music, but simply cannot cope with its content. They may oppose certain aspects of my work, but importantly not all aspects, they remain fans without agreeing with the message.” During their last tour in 2022, Tamara Lindemann hosted panel discussions where she invited fans – artists, politicians, academics, oil industry workers and activists who consider their position not radical, as well as activists who consider her own position is not radical enough. This does not mean, of course, that any of these people have automatically changed their position, that the conversations started through art have suddenly changed the political status quo, but it does provide grounds for rapprochement. Music, visual effects and performance not only support self-expression through texts, but also help build communities based on shared interests.

So perhaps this is another answer to the question of what art and literature can be. They can help a person process their emotions and become a way to overcome paralysis, a feeling of absolute depression, trauma; on a social level, they can help combat feelings of loneliness and isolation, and can bring people together into communities. The dire, real life challenges of today cannot be solved by art, of course, but neither can they be solved by a world full of hopeless, scared, isolated individuals. So maybe art is just the first step in a long chain of events and phenomena that can eventually push humanity to some decisions.

The first lecture was “More than Rust: Narrating Post-Industrial America” by Dr Julia Sattler from the Technical University of Dortmund (September 20, 2023).

The second lecture – “US Myths and Politics on the 21st-Century Stage: Hamilton: An American Musical” – was delivered by Hannah Schoch, researcher from the University of Zurich.

It should be recalled that three female students are studying at the ZEALAND Academy of Technology and Business in Denmark, female Polytechnic students talked about the peculiarities of studying at the Vilnius college, second-year student Mariia Bovkun is studying under the Erasmus+ credit academic mobility programme at the Wiener Neustadt University of Applied Sciences, 2 female Polytechnic students are studying at the Austrian University of Applied Sciences Sciences FH Burgenland, five female philology students completed internships at the international department of the “1 DECEMBRIE 1918” University of Alba Iulia, 15 female Polytechnic students studied for six months under the Erasmus+ long-term academic mobility programme at the “1 DECEMBRIE 1918” University of Alba Iulia (city Alba Iulia, Transylvania, Romania), during which they not only directly studied the subjects of their specialty, but also went through educational practice and travelled around Romania and Europe, five Polytechnic students during the spring semester studied under the Erasmus+ long-term academic mobility programme at the Institute of Transport and Telecommunications (Transport and Telecommunication Institute) in the city of Riga, Latvia, where they combined studies with traveling and learning new languages and cultures.

Media Center of

National University “Yuri Kondratyuk Poltava Polytechnic”